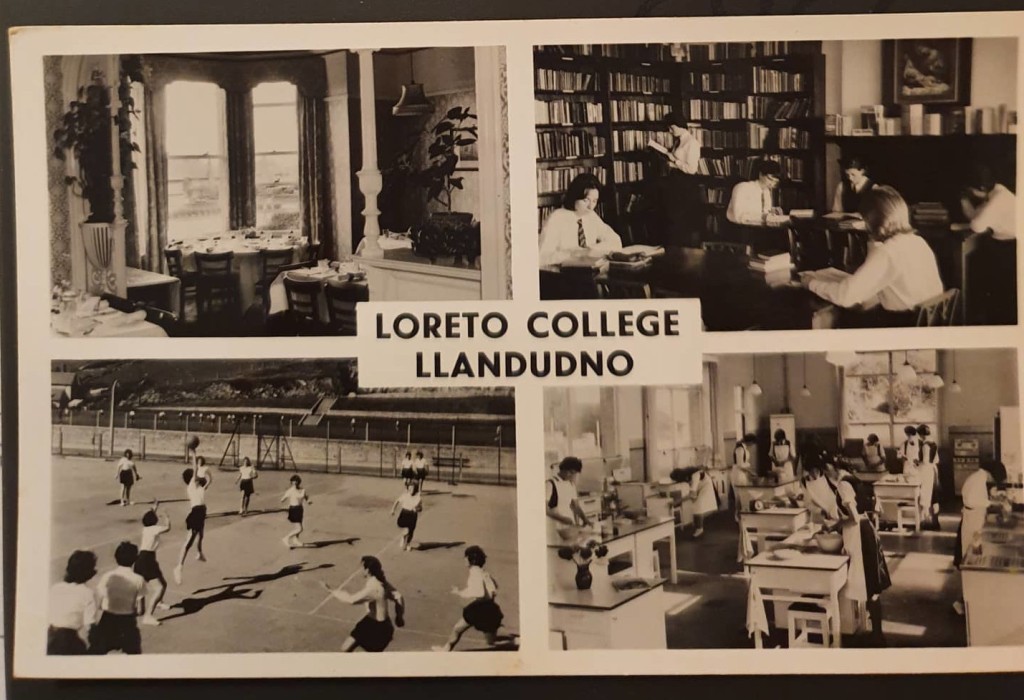

I recently discovered that the convent boarding school I attended in Llandudno from 1959 to 1963, run by Irish nuns, has been turned into the ‘Loreto Spirituality Centre‘ offering ‘retreats, conferences and quiet time’.

On their programme for 2024 is a 3-day event entitled The Sea Within – Wellbeing and Sandplay for a Changing Era offering ‘a relaxing and refreshing space to get in touch with your own inner resources and gifts through sandplay, poetry, quiet meditation and stillness, and incorporating Wellbeing practices such as Tai Chi, self-acupressure, and Circle Dance’

I am still in touch with several former classmates, bonded by common memories in which the petty cruelties of some of the more sadistic nuns, the disgustingness of the food and the suppression of any expressions of individuality feature large. Although widely scattered geographically, we have been having instant-messenger-enabled fun imagining what the nuns we knew back then would make of all this. ‘Jesus, Mary and Joseph!’ we imagine Mother Anthony expostulating. She was one of several who repeatedly told us off for ‘daydreaming’ (a term that you might think encompasses just about every activity this retreat is designed to encourage). ’Daydreaming’ was defined broadly, even including redirecting your gaze from the textbook (in which you had already finished all the homework that had been set) to a window to follow the flight of a seagull or wearing an expression that provoked the response ‘And you can take that look off your face’. On one occasion, when I had obviously failed to manage my body language appropriately, she followed this up with ‘God help the man who gets you, Ursula Huws!’

Or Mother Rita, not the sharpest knife in the box, who was assigned roles teaching topics for which she had little aptitude, including art, and often let cats out of bags. I recall a typical interaction which went something like this:

Mother Rita writes a statement on the blackboard with an error in it.

Pupil (rashly) puts up hand.

Mother Rita: ‘Well, Noticebox, what is it now?’

Pupil starts to point out said error. Observing the look of fury dawning on Mother Rita’s face she backs down, ‘Well I just thought….’ and tails off.

Mother Rita: ‘You thought, you thought? You’re not hear to think young lady, You’re here to learn obedience and be a good Catholic wife and mother’.

As for playing in the sand and dancing in circles, Well, whatever next! It is true that the convent was right next to the sea and we were all required to do a brisk walk every morning ‘around the lake’ (the ‘lake’ being a shallow paddling pool on the West Shore Promenade) but there was certainly no play: we had to stay in tight formation, walking in pairs in a crocodile topped and tailed by a nun. No breaking of ranks and certainly no relaxing! Idleness was as dangerous a crime as daydreaming or thinking.

Even Mother Mary of the Rosary, the runaway favourite in most of our shared memories, discouraged too much independent contemplation. When I confided that I’d like to study philosophy at university she advised strongly against it on the grounds that it would lead me to ‘lose the faith’.

(Here it is only fair to note that many of these nuns had probably been pushed into joining the order in their teens under who knows what pressures and may merely have been echoing familial views they had grown up with. I learned the backstory of one novice, through a family connection. Her parents, converts from Judaism, were determined to ‘give a child to God’ and the lot fell on her after her older brothers, one by one, had all dropped out of seminaries)

So does this conversion to a retreat represent a complete turnaround? On the face of it, yes. But, as one of my fellow-survivors shrewdly pointed out, you could equally well look at it as the continuation of the same old strategy of making money by giving the paying public what they want, leveraging the order’s religious values for whatever they are worth. Back in the mid-20th century, convents were able to exploit middle class parents’ desire to outsource the difficult parts of childcare by persuading them that the children would be instilled with good Christian values, including obedience to authority and the ability to focus on deferred gratification, and moulded to the prevailing societal political and social norms.

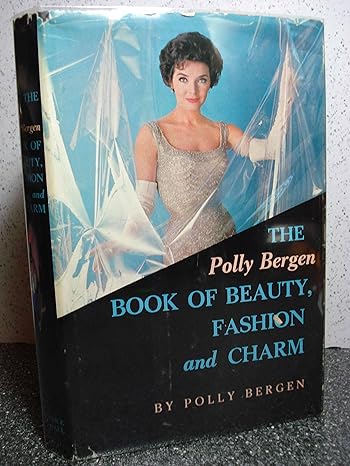

What the nuns promised these mostly conservative parents was a balance that was well-nigh impossible even then and was shortly to become completely so. On the one hand, their daughters would be equipped with the manners and attributes that would enable them to ensnare a husband while, on the other, they would be able to preserve their purity – a major challenge given the oft-emphasised assertion of how impossible it was for men to resist their urges if they were overly provoked. Girls thus had a double responsibility – to charm, but not tempt! (and, by implication, they were also to blame if either strategy failed – whether they were dumped for being insufficiently seductive or raped for being overly so).

In pursuit of these contradictory goals, we were each presented in 1962 with a copy of a ‘book of charm’ (see picture) but were also forbidden to wear patent leather shoes in case lustful boys might be aroused by seeing a reflection of our knickers in them. And told that it was a mortal sin to use menstrual tampons. Meanwhile we were warned regularly from the pulpit of the dangers of communism (the convent had its own chapel and resident chaplain).

Now in the 21st century, you might think that all of these values have been overturned. But there seems to be one constant. Those wily nuns are still generating an income from pandering to the dominant values of conservative middle-class consumers – still monetising their holiness. After several decades of public exposure of a range of horrors (including the Magdalene nurseries in Ireland, snatching of babies from single mothers, separation of indigenous children from their parents, forced child migration, sexual abuse) it is no longer possible to present the catholic church as occupying any kind of moral high ground, but ‘spirituality’ has found a new social role. Along with ‘mindfulness’, ‘meditation’, ‘positivity’ and ”personal growth’ it has become an essential tool in the battle for ‘wellbeing’ in the crisis of ‘mental health’ which is currently regarded as one of the greatest ill of our times.

Unhappiness, these days, it seems, is no longer understood as the consequence of personal misfortune (such as a debilitating illness or a bereavement or social ills (such as poverty or homelessness) or, heaven forbid, the result of an unpleasant working environment (with long working hours, monotonous processes, impossible-to-meet targets or precariousness). It is not, in other words, something whose causes we should be trying to address. No, it is seen as something which it is essentially our own responsibility to cope with – and our own fault if we fail to do so. If we cannot manage to handle these contradictions on our own (just as parents in the 1950s could not handle the contradictions of bringing up teenagers in an increasingly consumerist society) then solutions must be provided in the market.

If you are poor, this might be via an app on your phone or a standardised course of therapy supplied by your employer, the NHS or a project designed to get you back to work (increasingly likely to be provided via an online platform in which you are matched by AI with a precariously-employed therapist, in a process described by Elizabeth Cotton as ‘the uberisation of therapy’ or ‘therapeutic Tinder‘). If you are better off, then you can afford to combine it with something like a weekend retreat – a holiday break with creature comforts in pleasant surroundings in which you can be reassured that no rebellious thoughts are likely to interrupt the process of massaging your soul back into alignment with contemporary capitalism.

It is therefore perhaps not surprising – though nevertheless depressing – that this new accommodation of suffering individuals to the status quo should be taking place within those same walls in Llandudno that saw so much human misery when I was young. But you have to hand it to those nuns – despite their discouragement of our youthful inventiveness, they are nothing if not entrepreneurial when it comes to their own commercial future.